4. Replication

The replication problem is one of many problems in distributed systems. I've chosen to focus on it over other problems such as leader election, failure detection, mutual exclusion, consensus and global snapshots because it is often the part that people are most interested in. One way in which parallel databases are differentiated is in terms of their replication features, for example. Furthermore, replication provides a context for many subproblems, such as leader election, failure detection, consensus and atomic broadcast.

Replication is a group communication problem. What arrangement and communication pattern gives us the performance and availability characteristics we desire? How can we ensure fault tolerance, durability and non-divergence in the face of network partitions and simultaneous node failure?

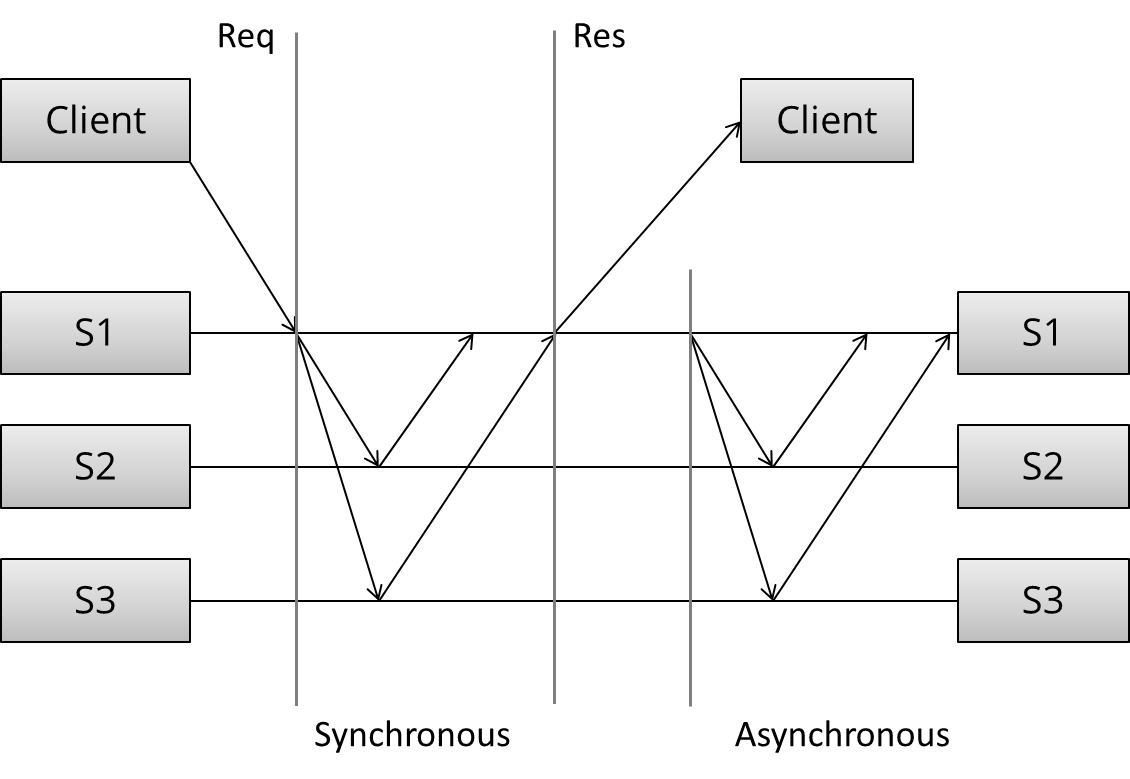

Again, there are many ways to approach replication. The approach I'll take here just looks at high level patterns that are possible for a system with replication. Looking at this visually helps keep the discussion focused on the overall pattern rather than the specific messaging involved. My goal here is to explore the design space rather than to explain the specifics of each algorithm.

Let's first define what replication looks like. We assume that we have some initial database, and that clients make requests which change the state of the database.

The arrangement and communication pattern can then be divided into several stages:

- (Request) The client sends a request to a server

- (Sync) The synchronous portion of the replication takes place

- (Response) A response is returned to the client

- (Async) The asynchronous portion of the replication takes place

This model is loosely based on this article. Note that the pattern of messages exchanged in each portion of the task depends on the specific algorithm: I am intentionally trying to get by without discussing the specific algorithm.

Given these stages, what kind of communication patterns can we create? And what are the performance and availability implications of the patterns we choose?

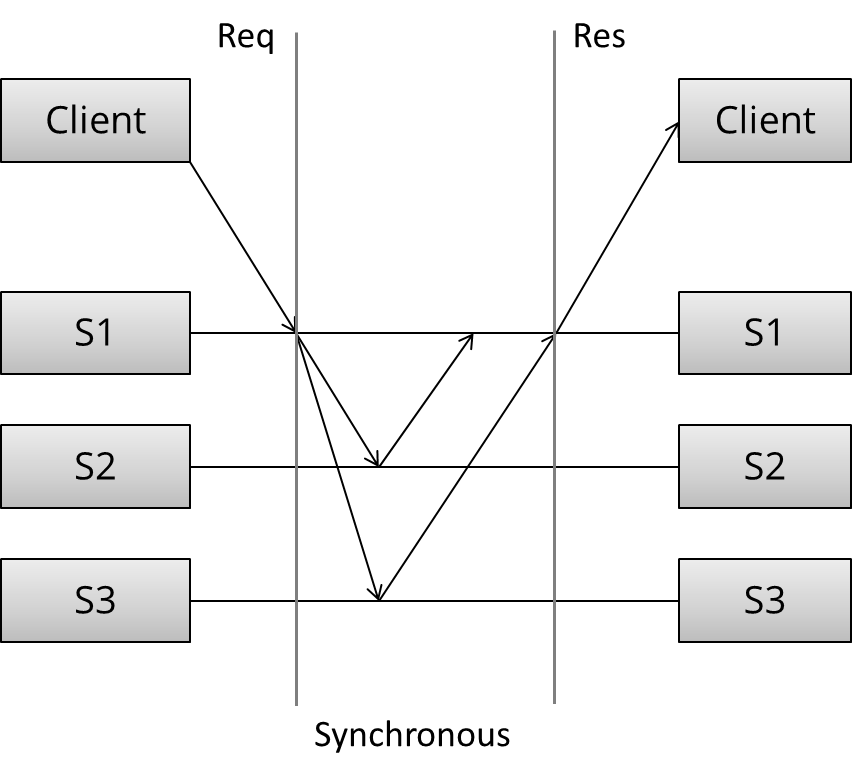

Synchronous replication

The first pattern is synchronous replication (also known as active, or eager, or push, or pessimistic replication). Let's draw what that looks like:

Here, we can see three distinct stages: first, the client sends the request. Next, what we called the synchronous portion of replication takes place. The term refers to the fact that the client is blocked - waiting for a reply from the system.

During the synchronous phase, the first server contacts the two other servers and waits until it has received replies from all the other servers. Finally, it sends a response to the client informing it of the result (e.g. success or failure).

All this seems straightforward. What can we say of this specific arrangement of communication patterns, without discussing the details of the algorithm during the synchronous phase? First, observe that this is a write N - of - N approach: before a response is returned, it has to be seen and acknowledged by every server in the system.

From a performance perspective, this means that the system will be as fast as the slowest server in it. The system will also be very sensitive to changes in network latency, since it requires every server to reply before proceeding.

Given the N-of-N approach, the system cannot tolerate the loss of any servers. When a server is lost, the system can no longer write to all the nodes, and so it cannot proceed. It might be able to provide read-only access to the data, but modifications are not allowed after a node has failed in this design.

This arrangement can provide very strong durability guarantees: the client can be certain that all N servers have received, stored and acknowledged the request when the response is returned. In order to lose an accepted update, all N copies would need to be lost, which is about as good a guarantee as you can make.

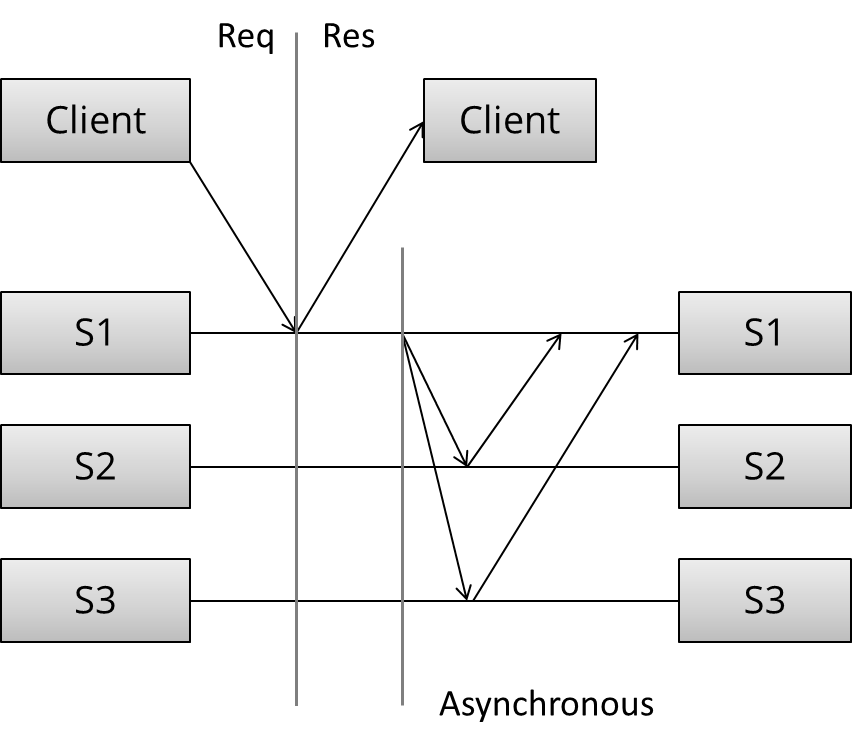

Asynchronous replication

Let's contrast this with the second pattern - asynchronous replication (a.k.a. passive replication, or pull replication, or lazy replication). As you may have guessed, this is the opposite of synchronous replication:

Here, the master (/leader / coordinator) immediately sends back a response to the client. It might at best store the update locally, but it will not do any significant work synchronously and the client is not forced to wait for more rounds of communication to occur between the servers.

At some later stage, the asynchronous portion of the replication task takes place. Here, the master contacts the other servers using some communication pattern, and the other servers update their copies of the data. The specifics depend on the algorithm in use.

What can we say of this specific arrangement without getting into the details of the algorithm? Well, this is a write 1 - of - N approach: a response is returned immediately and update propagation occurs sometime later.

From a performance perspective, this means that the system is fast: the client does not need to spend any additional time waiting for the internals of the system to do their work. The system is also more tolerant of network latency, since fluctuations in internal latency do not cause additional waiting on the client side.

This arrangement can only provide weak, or probabilistic durability guarantees. If nothing goes wrong, the data is eventually replicated to all N machines. However, if the only server containing the data is lost before this can take place, the data is permanently lost.

Given the 1-of-N approach, the system can remain available as long as at least one node is up (at least in theory, though in practice the load will probably be too high). A purely lazy approach like this provides no durability or consistency guarantees; you may be allowed to write to the system, but there are no guarantees that you can read back what you wrote if any faults occur.

Finally, it's worth noting that passive replication cannot ensure that all nodes in the system always contain the same state. If you accept writes at multiple locations and do not require that those nodes synchronously agree, then you will run the risk of divergence: reads may return different results from different locations (particularly after nodes fail and recover), and global constraints (which require communicating with everyone) cannot be enforced.

I haven't really mentioned the communication patterns during a read (rather than a write), because the pattern of reads really follows from the pattern of writes: during a read, you want to contact as few nodes as possible. We'll discuss this a bit more in the context of quorums.

We've only discussed two basic arrangements and none of the specific algorithms. Yet we've been able to figure out quite a bit of about the possible communication patterns as well as their performance, durability guarantees and availability characteristics.

An overview of major replication approaches

Having discussed the two basic replication approaches: synchronous and asynchronous replication, let's have a look at the major replication algorithms.

There are many, many different ways to categorize replication techniques. The second distinction (after sync vs. async) I'd like to introduce is between:

- Replication methods that prevent divergence (single copy systems) and

- Replication methods that risk divergence (multi-master systems)

The first group of methods has the property that they "behave like a single system". In particular, when partial failures occur, the system ensures that only a single copy of the system is active. Furthermore, the system ensures that the replicas are always in agreement. This is known as the consensus problem.

Several processes (or computers) achieve consensus if they all agree on some value. More formally:

- Agreement: Every correct process must agree on the same value.

- Integrity: Every correct process decides at most one value, and if it decides some value, then it must have been proposed by some process.

- Termination: All processes eventually reach a decision.

- Validity: If all correct processes propose the same value V, then all correct processes decide V.

Mutual exclusion, leader election, multicast and atomic broadcast are all instances of the more general problem of consensus. Replicated systems that maintain single copy consistency need to solve the consensus problem in some way.

The replication algorithms that maintain single-copy consistency include:

- 1n messages (asynchronous primary/backup)

- 2n messages (synchronous primary/backup)

- 4n messages (2-phase commit, Multi-Paxos)

- 6n messages (3-phase commit, Paxos with repeated leader election)

These algorithms vary in their fault tolerance (e.g. the types of faults they can tolerate). I've classified these simply by the number of messages exchanged during an execution of the algorithm, because I think it is interesting to try to find an answer to the question "what are we buying with the added message exchanges?"

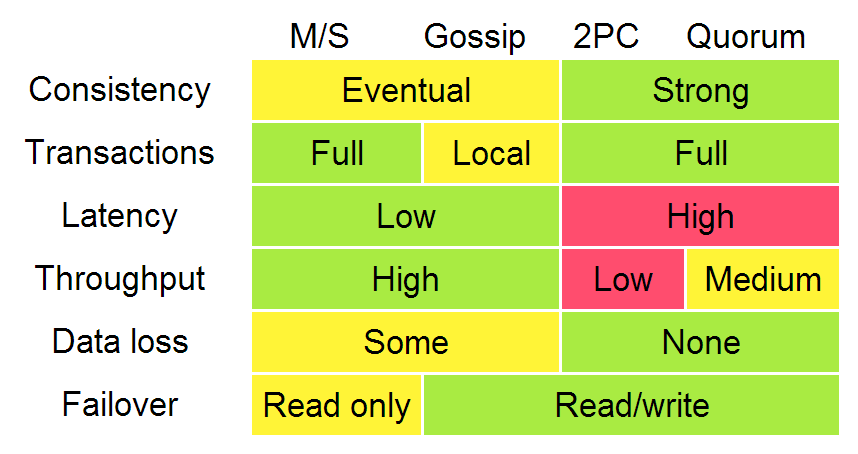

The diagram below, adapted from Ryan Barret at Google, describes some of the aspects of the different options:

The consistency, latency, throughput, data loss and failover characteristics in the diagram above can really be traced back to the two different replication methods: synchronous replication (e.g. waiting before responding) and asynchronous replication. When you wait, you get worse performance but stronger guarantees. The throughput difference between 2PC and quorum systems will become apparent when we discuss partition (and latency) tolerance.

In that diagram, algorithms enforcing weak (/eventual) consistency are lumped up into one category ("gossip"). However, I will discuss replication methods for weak consistency - gossip and (partial) quorum systems - in more detail. The "transactions" row really refers more to global predicate evaluation, which is not supported in systems with weak consistency (though local predicate evaluation can be supported).

It is worth noting that systems enforcing weak consistency requirements have fewer generic algorithms, and more techniques that can be selectively applied. Since systems that do not enforce single-copy consistency are free to act like distributed systems consisting of multiple nodes, there are fewer obvious objectives to fix and the focus is more on giving people a way to reason about the characteristics of the system that they have.

For example:

- Client-centric consistency models attempt to provide more intelligible consistency guarantees while allowing for divergence.

- CRDTs (convergent and commutative replicated datatypes) exploit semilattice properties (associativity, commutativity, idempotency) of certain state and operation-based data types.

- Confluence analysis (as in the Bloom language) uses information regarding the monotonicity of computations to maximally exploit disorder.

- PBS (probabilistically bounded staleness) uses simulation and information collected from a real world system to characterize the expected behavior of partial quorum systems.

I'll talk about all of these a bit further on, first; let's look at the replication algorithms that maintain single-copy consistency.

Primary/backup replication

Primary/backup replication (also known as primary copy replication master-slave replication or log shipping) is perhaps the most commonly used replication method, and the most basic algorithm. All updated are performed on the primary, and a log of operations (or alternatively, changes) is shipped across the network to the backup replicas. There are two variants:

- asynchronous primary/backup replication and

- synchronous primary/backup replication

The synchronous version requires two messages ("update" + "acknowledge receipt") while the asynchronous version could run with just one ("update").

P/B is very common. For example, by default MySQL replication uses the asynchronous variant. MongoDB also uses P/B (with some additional procedures for failover). All operations are performed on one master server, which serializes them to a local log, which is then replicated asynchronously to the backup servers.

As we discussed earlier in the context of asynchronous replication, any asynchronous replication algorithm can only provide weak durability guarantees. In MySQL replication this manifests as replication lag: the asynchronous backups are always at least one operation behind the primary. If the primary fails, then the updates that have not yet been sent to the backups are lost.

The synchronous variant of primary/backup replication ensures that writes have been stored on other nodes before returning back to the client - at the cost of waiting for responses from other replicas. However, it is worth noting that even this variant can only offer weak guarantees. Consider the following simple failure scenario:

- the primary receives a write and sends it to the backup

- the backup persists and ACKs the write

- and then primary fails before sending ACK to the client

The client now assumes that the commit failed, but the backup committed it; if the backup is promoted to primary, it will be incorrect. Manual cleanup may be needed to reconcile the failed primary or divergent backups.

I am simplifying here of course. While all primary/backup replication algorithms follow the same general messaging pattern, they differ in their handling of failover, replicas being offline for extended periods and so on. However, it is not possible to be resilient to inopportune failures of the primary in this scheme.

What is key in the log-shipping / primary/backup based schemes is that they can only offer a best-effort guarantee (e.g. they are susceptible to lost updates or incorrect updates if nodes fail at inopportune times). Furthermore, P/B schemes are susceptible to split-brain, where the failover to a backup kicks in due to a temporary network issue and causes both the primary and backup to be active at the same time.

To prevent inopportune failures from causing consistency guarantees to be violated; we need to add another round of messaging, which gets us the two phase commit protocol (2PC).

Two phase commit (2PC)

Two phase commit (2PC) is a protocol used in many classic relational databases. For example, MySQL Cluster (not to be confused with the regular MySQL) provides synchronous replication using 2PC. The diagram below illustrates the message flow:

[ Coordinator ] -> OK to commit? [ Peers ]

<- Yes / No

[ Coordinator ] -> Commit / Rollback [ Peers ]

<- ACK

In the first phase (voting), the coordinator sends the update to all the participants. Each participant processes the update and votes whether to commit or abort. When voting to commit, the participants store the update onto a temporary area (the write-ahead log). Until the second phase completes, the update is considered temporary.

In the second phase (decision), the coordinator decides the outcome and informs every participant about it. If all participants voted to commit, then the update is taken from the temporary area and made permanent.

Having a second phase in place before the commit is considered permanent is useful, because it allows the system to roll back an update when a node fails. In contrast, in primary/backup ("1PC"), there is no step for rolling back an operation that has failed on some nodes and succeeded on others, and hence the replicas could diverge.

2PC is prone to blocking, since a single node failure (participant or coordinator) blocks progress until the node has recovered. Recovery is often possible thanks to the second phase, during which other nodes are informed about the system state. Note that 2PC assumes that the data in stable storage at each node is never lost and that no node crashes forever. Data loss is still possible if the data in the stable storage is corrupted in a crash.

The details of the recovery procedures during node failures are quite complicated so I won't get into the specifics. The major tasks are ensuring that writes to disk are durable (e.g. flushed to disk rather than cached) and making sure that the right recovery decisions are made (e.g. learning the outcome of the round and then redoing or undoing an update locally).

As we learned in the chapter regarding CAP, 2PC is a CA - it is not partition tolerant. The failure model that 2PC addresses does not include network partitions; the prescribed way to recover from a node failure is to wait until the network partition heals. There is no safe way to promote a new coordinator if one fails; rather a manual intervention is required. 2PC is also fairly latency-sensitive, since it is a write N-of-N approach in which writes cannot proceed until the slowest node acknowledges them.

2PC strikes a decent balance between performance and fault tolerance, which is why it has been popular in relational databases. However, newer systems often use a partition tolerant consensus algorithm, since such an algorithm can provide automatic recovery from temporary network partitions as well as more graceful handling of increased between-node latency.

Let's look at partition tolerant consensus algorithms next.

Partition tolerant consensus algorithms

Partition tolerant consensus algorithms are as far as we're going to go in terms of fault-tolerant algorithms that maintain single-copy consistency. There is a further class of fault tolerant algorithms: algorithms that tolerate arbitrary (Byzantine) faults; these include nodes that fail by acting maliciously. Such algorithms are rarely used in commercial systems, because they are more expensive to run and more complicated to implement - and hence I will leave them out.

When it comes to partition tolerant consensus algorithms, the most well-known algorithm is the Paxos algorithm. It is, however, notoriously difficult to implement and explain, so I will focus on Raft, a recent (~early 2013) algorithm designed to be easier to teach and implement. Let's first take a look at network partitions and the general characteristics of partition tolerant consensus algorithms.

What is a network partition?

A network partition is the failure of a network link to one or several nodes. The nodes themselves continue to stay active, and they may even be able to receive requests from clients on their side of the network partition. As we learned earlier - during the discussion of the CAP theorem - network partitions do occur and not all systems handle them gracefully.

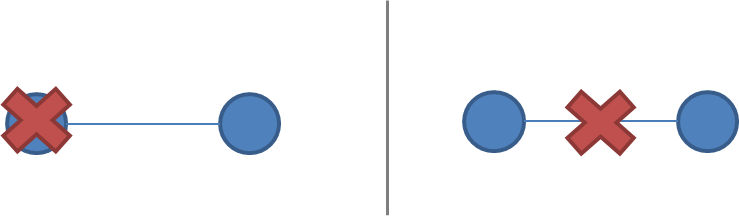

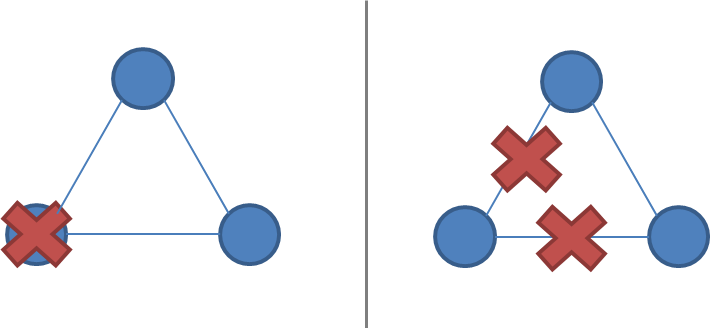

Network partitions are tricky because during a network partition, it is not possible to distinguish between a failed remote node and the node being unreachable. If a network partition occurs but no nodes fail, then the system is divided into two partitions which are simultaneously active. The two diagrams below illustrate how a network partition can look similar to a node failure.

A system of 2 nodes, with a failure vs. a network partition:

A system of 3 nodes, with a failure vs. a network partition:

A system that enforces single-copy consistency must have some method to break symmetry: otherwise, it will split into two separate systems, which can diverge from each other and can no longer maintain the illusion of a single copy.

Network partition tolerance for systems that enforce single-copy consistency requires that during a network partition, only one partition of the system remains active since during a network partition it is not possible to prevent divergence (e.g. CAP theorem).

Majority decisions

This is why partition tolerant consensus algorithms rely on a majority vote. Requiring a majority of nodes - rather than all of the nodes (as in 2PC) - to agree on updates allows a minority of the nodes to be down, or slow, or unreachable due to a network partition. As long as (N/2 + 1)-of-N nodes are up and accessible, the system can continue to operate.

Partition tolerant consensus algorithms use an odd number of nodes (e.g. 3, 5 or 7). With just two nodes, it is not possible to have a clear majority after a failure. For example, if the number of nodes is three, then the system is resilient to one node failure; with five nodes the system is resilient to two node failures.

When a network partition occurs, the partitions behave asymmetrically. One partition will contain the majority of the nodes. Minority partitions will stop processing operations to prevent divergence during a network partition, but the majority partition can remain active. This ensures that only a single copy of the system state remains active.

Majorities are also useful because they can tolerate disagreement: if there is a perturbation or failure, the nodes may vote differently. However, since there can be only one majority decision, a temporary disagreement can at most block the protocol from proceeding (giving up liveness) but it cannot violate the single-copy consistency criterion (safety property).

Roles

There are two ways one might structure a system: all nodes may have the same responsibilities, or nodes may have separate, distinct roles.

Consensus algorithms for replication generally opt for having distinct roles for each node. Having a single fixed leader or master server is an optimization that makes the system more efficient, since we know that all updates must pass through that server. Nodes that are not the leader just need to forward their requests to the leader.

Note that having distinct roles does not preclude the system from recovering from the failure of the leader (or any other role). Just because roles are fixed during normal operation doesn't mean that one cannot recover from failure by reassigning the roles after a failure (e.g. via a leader election phase). Nodes can reuse the result of a leader election until node failures and/or network partitions occur.

Both Paxos and Raft make use of distinct node roles. In particular, they have a leader node ("proposer" in Paxos) that is responsible for coordination during normal operation. During normal operation, the rest of the nodes are followers ("acceptors" or "voters" in Paxos).

Epochs

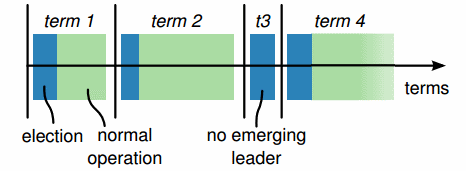

Each period of normal operation in both Paxos and Raft is called an epoch ("term" in Raft). During each epoch only one node is the designated leader (a similar system is used in Japan where era names change upon imperial succession).

After a successful election, the same leader coordinates until the end of the epoch. As shown in the diagram above (from the Raft paper), some elections may fail, causing the epoch to end immediately.

Epochs act as a logical clock, allowing other nodes to identify when an outdated node starts communicating - nodes that were partitioned or out of operation will have a smaller epoch number than the current one, and their commands are ignored.

Leader changes via duels

During normal operation, a partition-tolerant consensus algorithm is rather simple. As we've seen earlier, if we didn't care about fault tolerance, we could just use 2PC. Most of the complexity really arises from ensuring that once a consensus decision has been made, it will not be lost and the protocol can handle leader changes as a result of a network or node failure.

All nodes start as followers; one node is elected to be a leader at the start. During normal operation, the leader maintains a heartbeat which allows the followers to detect if the leader fails or becomes partitioned.

When a node detects that a leader has become non-responsive (or, in the initial case, that no leader exists), it switches to an intermediate state (called "candidate" in Raft) where it increments the term/epoch value by one, initiates a leader election and competes to become the new leader.

In order to be elected a leader, a node must receive a majority of the votes. One way to assign votes is to simply assign them on a first-come-first-served basis; this way, a leader will eventually be elected. Adding a random amount of waiting time between attempts at getting elected will reduce the number of nodes that are simultaneously attempting to get elected.

Numbered proposals within an epoch

During each epoch, the leader proposes one value at a time to be voted upon. Within each epoch, each proposal is numbered with a unique strictly increasing number. The followers (voters / acceptors) accept the first proposal they receive for a particular proposal number.

Normal operation

During normal operation, all proposals go through the leader node. When a client submits a proposal (e.g. an update operation), the leader contacts all nodes in the quorum. If no competing proposals exist (based on the responses from the followers), the leader proposes the value. If a majority of the followers accept the value, then the value is considered to be accepted.

Since it is possible that another node is also attempting to act as a leader, we need to ensure that once a single proposal has been accepted, its value can never change. Otherwise a proposal that has already been accepted might for example be reverted by a competing leader. Lamport states this as:

P2: If a proposal with value

vis chosen, then every higher-numbered proposal that is chosen has valuev.

Ensuring that this property holds requires that both followers and proposers are constrained by the algorithm from ever changing a value that has been accepted by a majority. Note that "the value can never change" refers to the value of a single execution (or run / instance / decision) of the protocol. A typical replication algorithm will run multiple executions of the algorithm, but most discussions of the algorithm focus on a single run to keep things simple. We want to prevent the decision history from being altered or overwritten.

In order to enforce this property, the proposers must first ask the followers for their (highest numbered) accepted proposal and value. If the proposer finds out that a proposal already exists, then it must simply complete this execution of the protocol, rather than making its own proposal. Lamport states this as:

P2b. If a proposal with value

vis chosen, then every higher-numbered proposal issued by any proposer has valuev.

More specifically:

P2c. For any

vandn, if a proposal with valuevand numbernis issued [by a leader], then there is a setSconsisting of a majority of acceptors [followers] such that either (a) no acceptor inShas accepted any proposal numbered less thann, or (b)vis the value of the highest-numbered proposal among all proposals numbered less thannaccepted by the followers inS.

This is the core of the Paxos algorithm, as well as algorithms derived from it. The value to be proposed is not chosen until the second phase of the protocol. Proposers must sometimes simply retransmit a previously made decision to ensure safety (e.g. clause b in P2c) until they reach a point where they know that they are free to impose their own proposal value (e.g. clause a).

If multiple previous proposals exist, then the highest-numbered proposal value is proposed. Proposers may only attempt to impose their own value if there are no competing proposals at all.

To ensure that no competing proposals emerge between the time the proposer asks each acceptor about its most recent value, the proposer asks the followers not to accept proposals with lower proposal numbers than the current one.

Putting the pieces together, reaching a decision using Paxos requires two rounds of communication:

[ Proposer ] -> Prepare(n) [ Followers ]

<- Promise(n; previous proposal number

and previous value if accepted a

proposal in the past)

[ Proposer ] -> AcceptRequest(n, own value or the value [ Followers ]

associated with the highest proposal number

reported by the followers)

<- Accepted(n, value)

The prepare stage allows the proposer to learn of any competing or previous proposals. The second phase is where either a new value or a previously accepted value is proposed. In some cases - such as if two proposers are active at the same time (dueling); if messages are lost; or if a majority of the nodes have failed - then no proposal is accepted by a majority. But this is acceptable, since the decision rule for what value to propose converges towards a single value (the one with the highest proposal number in the previous attempt).

Indeed, according to the FLP impossibility result, this is the best we can do: algorithms that solve the consensus problem must either give up safety or liveness when the guarantees regarding bounds on message delivery do not hold. Paxos gives up liveness: it may have to delay decisions indefinitely until a point in time where there are no competing leaders, and a majority of nodes accept a proposal. This is preferable to violating the safety guarantees.

Of course, implementing this algorithm is much harder than it sounds. There are many small concerns which add up to a fairly significant amount of code even in the hands of experts. These are issues such as:

- practical optimizations:

- avoiding repeated leader election via leadership leases (rather than heartbeats)

- avoiding repeated propose messages when in a stable state where the leader identity does not change

- ensuring that followers and proposers do not lose items in stable storage and that results stored in stable storage are not subtly corrupted (e.g. disk corruption)

- enabling cluster membership to change in a safe manner (e.g. base Paxos depends on the fact that majorities always intersect in one node, which does not hold if the membership can change arbitrarily)

- procedures for bringing a new replica up to date in a safe and efficient manner after a crash, disk loss or when a new node is provisioned

- procedures for snapshotting and garbage collecting the data required to guarantee safety after some reasonable period (e.g. balancing storage requirements and fault tolerance requirements)

Google's Paxos Made Live paper details some of these challenges.

Partition-tolerant consensus algorithms: Paxos, Raft, ZAB

Hopefully, this has given you a sense of how a partition-tolerant consensus algorithm works. I encourage you to read one of the papers in the further reading section to get a grasp of the specifics of the different algorithms.

Paxos. Paxos is one of the most important algorithms when writing strongly consistent partition tolerant replicated systems. It is used in many of Google's systems, including the Chubby lock manager used by BigTable/Megastore, the Google File System as well as Spanner.

Paxos is named after the Greek island of Paxos, and was originally presented by Leslie Lamport in a paper called "The Part-Time Parliament" in 1998. It is often considered to be difficult to implement, and there have been a series of papers from companies with considerable distributed systems expertise explaining further practical details (see the further reading). You might want to read Lamport's commentary on this issue here and here.

The issues mostly relate to the fact that Paxos is described in terms of a single round of consensus decision making, but an actual working implementation usually wants to run multiple rounds of consensus efficiently. This has led to the development of many extensions on the core protocol that anyone interested in building a Paxos-based system still needs to digest. Furthermore, there are additional practical challenges such as how to facilitate cluster membership change.

ZAB. ZAB - the Zookeeper Atomic Broadcast protocol is used in Apache Zookeeper. Zookeeper is a system which provides coordination primitives for distributed systems, and is used by many Hadoop-centric distributed systems for coordination (e.g. HBase, Storm, Kafka). Zookeeper is basically the open source community's version of Chubby. Technically speaking atomic broadcast is a problem different from pure consensus, but it still falls under the category of partition tolerant algorithms that ensure strong consistency.

Raft. Raft is a recent (2013) addition to this family of algorithms. It is designed to be easier to teach than Paxos, while providing the same guarantees. In particular, the different parts of the algorithm are more clearly separated and the paper also describes a mechanism for cluster membership change. It has recently seen adoption in etcd inspired by ZooKeeper.

Replication methods with strong consistency

In this chapter, we took a look at replication methods that enforce strong consistency. Starting with a contrast between synchronous work and asynchronous work, we worked our way up to algorithms that are tolerant of increasingly complex failures. Here are some of the key characteristics of each of the algorithms:

Primary/Backup

- Single, static master

- Replicated log, slaves are not involved in executing operations

- No bounds on replication delay

- Not partition tolerant

- Manual/ad-hoc failover, not fault tolerant, "hot backup"

2PC

- Unanimous vote: commit or abort

- Static master

- 2PC cannot survive simultaneous failure of the coordinator and a node during a commit

- Not partition tolerant, tail latency sensitive

Paxos

- Majority vote

- Dynamic master

- Robust to n/2-1 simultaneous failures as part of protocol

- Less sensitive to tail latency

Further reading

Primary-backup and 2PC

- Replication techniques for availability - Robbert van Renesse & Rachid Guerraoui, 2010

- Concurrency Control and Recovery in Database Systems

Paxos

- The Part-Time Parliament - Leslie Lamport

- Paxos Made Simple - Leslie Lamport, 2001

- Paxos Made Live - An Engineering Perspective - Chandra et al

- Paxos Made Practical - Mazieres, 2007

- Revisiting the Paxos Algorithm - Lynch et al

- How to build a highly available system with consensus - Butler Lampson

- Reconfiguring a State Machine - Lamport et al - changing cluster membership

- Implementing Fault-Tolerant Services Using the State Machine Approach: a Tutorial - Fred Schneider

Raft and ZAB

- In Search of an Understandable Consensus Algorithm, Diego Ongaro, John Ousterhout, 2013

- Raft Lecture - User Study

- A simple totally ordered broadcast protocol - Junqueira, Reed, 2008

- ZooKeeper Atomic Broadcast - Reed, 2011